An exorcism on paper

Martin Crowe's autobiography is an admirable, and brutal, effort at self-assessment

Andrew Alderson

02-Nov-2013

Getty Images

One word screams from the 303 thoroughly readable pages of Martin Crowe's second autobiography Raw: cathartic.

Crowe has laid his soul bare, grappling with the demons that plagued his career from pitch to television studio to battling lymphoma. Cricket took him from a teenage prodigy to a man who has reached his half-century (Crowe is now 51). Raw leaves the impression he feels both fulfilled and haunted by the experience.

Crowe writes of himself: "that innocent boy became a man who harboured grudges, he became the world record holder for grievances" and later says it was an "ongoing problem of mine - a disconnected spirit and soul overwhelmed by the ego and the emotional instability created from my unfinished teenage development".

The book's title quickly appears apt.

The opening acknowledgements indicate the onset of wisdom and humility. Crowe collaborated with veteran sportswriter Joseph Romanos, who wrote Tortured Genius, an unauthorised biography of him, in 1995. Crowe released his first memoir, Out On a Limb, the same year. He admits Romanos' effort was "more of an accurate story of my life than my own autobiography. He could

see what I couldn't." There is also a touching foreword from former Auckland Grammar School classmate and future All Black rugby great Grant Fox. The pair met in third form at the start of 1976.

Crowe is to be admired for unleashing such a brutal self-assessment. He is without peer as a thinker on cricket, in New Zealand if not the world. No one locally compares with Crowe for articulating opinions with such aplomb. Glenn Turner, Jeremy Coney, Bruce Edgar and Dion Nash would be among those to occupy the next tier. Yet Crowe, steeped in the game's history through his late father Dave, has the ability to consistently generate an "I wish I'd thought of that" response - especially when it comes to technique and the "big picture" for the international game.

Examples include his views on the Test championship, an assessment of Brendon McCullum's batting and of Muttiah Muralitharan's legacy, a breakdown of Stephen Fleming's career at home and abroad, and thoughts on how cricket should best use technology. Crowe was a deserved choice to deliver the annual Cowdrey lecture at Lord's in 2006.

He has seldom refrained from speaking his mind. However, such forthright convictions and a reluctance to compromise can inevitably lead to isolation and a reputation for being difficult, as Crowe readily admits in the book. Sadly, if this book is to be believed, his input to cricket will cease. He writes: "Cricket gave me the tools, the lessons and the experience. But after 50 years it won't anymore. Goodbye cricket. Thanks for the memories."

Who knows what Crowe will do, but if he has second thoughts, one compromise could be to continue as a media columnist, where he wouldn't have to deal directly with the barbs. He could simply state his case from an objective distance. In doing so he could still influence future generations. For instance, New Zealand's top-order batsmen would have been fools not to have read his memorable advice last year on this site ahead of their win in the second Test in Sri Lanka.

Crowe's creative energies also shouldn't be allowed to go to waste. Anyone whose innovations include setting up Cricket Max (a precursor to T20) in the 1990s or telecasting First XV rugby matches to boost subscriber levels on the Rugby Channel is a powerhouse for idea generation.

"Cricket gave me the tools, the lessons and the experience. But after 50 years it won't anymore. Goodbye cricket. Thanks for the memories"Martin Crowe

Perhaps Crowe has made the right decision to divorce himself from the fray if this statement is anything to judge it on: "I want to live a life that is fearless, that is without judgement or scrutiny, let alone have any negative emotions of hate, resentment or grievance. I am so tired of that life, of fighting, of ego, of trying to win opinion and of needing acceptance."

Hopefully that attitude will extend to his desire to alleviate baldness. It seems extraordinary that someone of Crowe's standing in New Zealand society could be worried by such a minor issue. He's not alone in this obsession among former cricketers, but baldness is hardly a social hindrance these days, if it ever was. Exhibit A would be his brother Jeff, who appears no less robust, healthy or virile for lacking a rug.

Raw is brimming with pain, from which it appears Crowe has now found a release. The "rebirthing" episode at an outfit called Camp Eden in a Queensland forest sounded particularly harrowing, as did having to deal with the twin "nasty snakes" of cancer and New Zealand Cricket's demotion of his friend Taylor as captain. Crowe's wife Lorraine Downes and daughter Emma Louise appear to have acted as the ultimate panaceas. Through them he appears to have found the strength to deal with his new world.

Fortunately, readers get some light and shade away from the window on Crowe's anguish. The book looks at his favourite players, and there is an intriguing chapter, "The Dream Test", where his imagination lights up the page.

Crowe's cavernous knowledge produces erudite appraisals on the greatest cricketers of all time. This reviewer found the best were those of whom Crowe could offer personal anecdotes, such as seeing the whites of Andy Roberts' eyes, Wasim Akram's bouncers grazing his mouth and forcing the installation of a grill, and Dennis Lillee's advice of "Don't ever f****** walk again", when Crowe turned on his heel as a 19-year-old in his first Test series after offering a catch to short leg.

There is also welcome self-deprecation about the time his job at Sky Television was affected by a restructure. Chief executive John Fellet apparently said, "Play with the cards you're dealt." Crowe says he looked into his bare hands and visualised a pair of twos.

The Dream Test concept is difficult to pull off with credibility but purists - or anyone who has pitted world-renowned figures against each other in the backyard - will understand what Crowe is getting at. Everything from Don Bradman finishing on 111 to Adam Gilchrist walking, to Tony Greig prodding the pitch with his car keys makes an appearance, as the 1877-1961 Black and Whites (based on the colour of the media coverage) meet the Colours (1962-2013) at Lord's. The delineation is based on the year of

Crowe's birth.

Crowe deserves thanks for offering an enlightening insight into his unique world. Cricket will be the lesser if there's no reconciliation between him and the game.

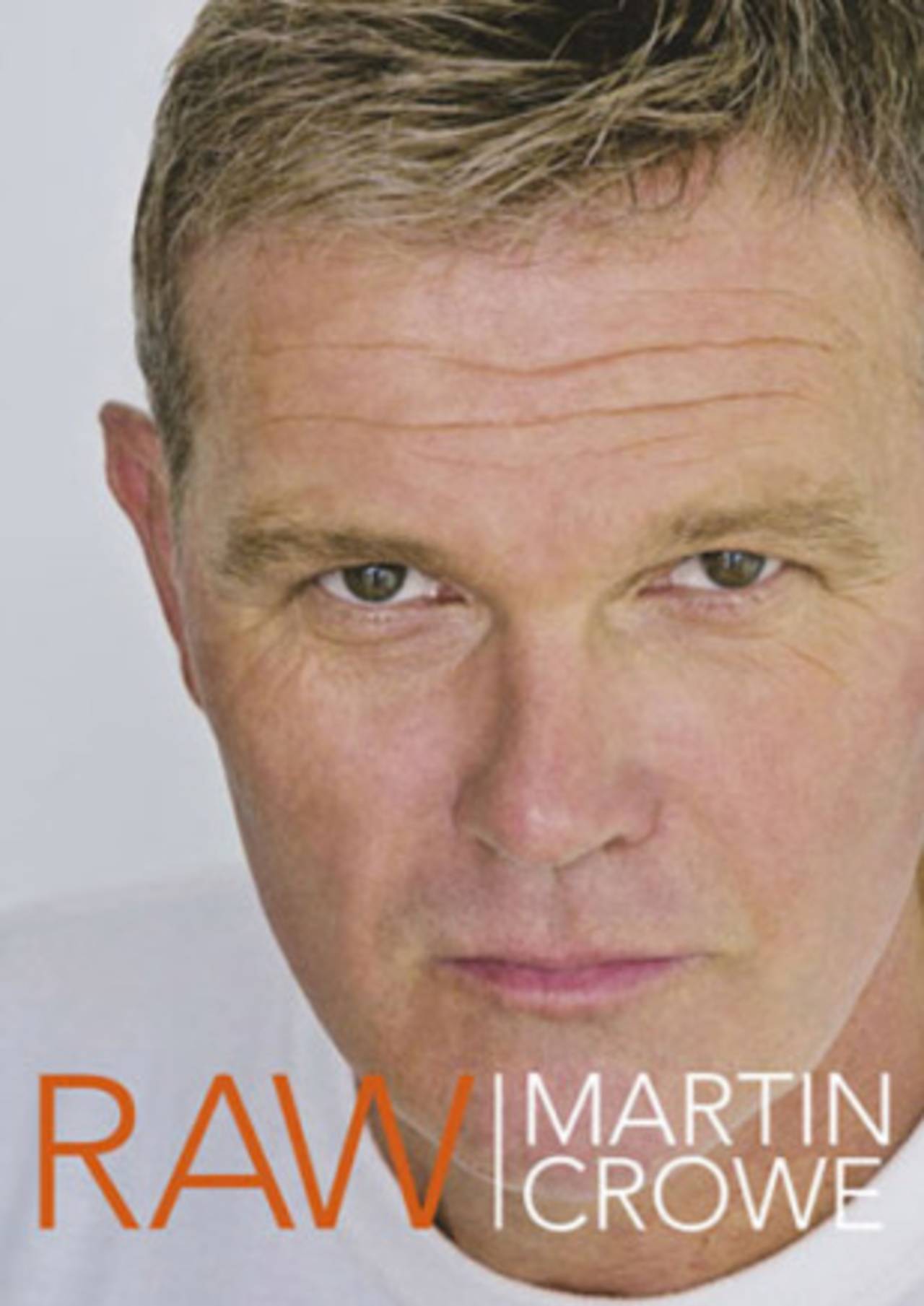

Raw

Martin Crowe

Trio Books

309 pages, NZ$39.95

Martin Crowe

Trio Books

309 pages, NZ$39.95

Andrew Alderson is cricket writer at New Zealand's Herald on Sunday