For the past 40 years or more Scyld Berry has been one of cricket's most erudite and distinguished writers. Whether as a cricket correspondent of the Sunday Telegraph or as an editor of Wisden, he has reflected on the game with depth and originality.

His multifarious musings have been brought together in Cricket: The Game of Life, which is essentially a consolidation of the historical research, reveries and suppositions that have sustained him over a lifetime. Berry believes that cricket is worthy of serious contemplation on many levels - it has brought structure to his life since childhood - and all those who ponder widely upon the game's qualities will find many elevating thoughts to detain them.

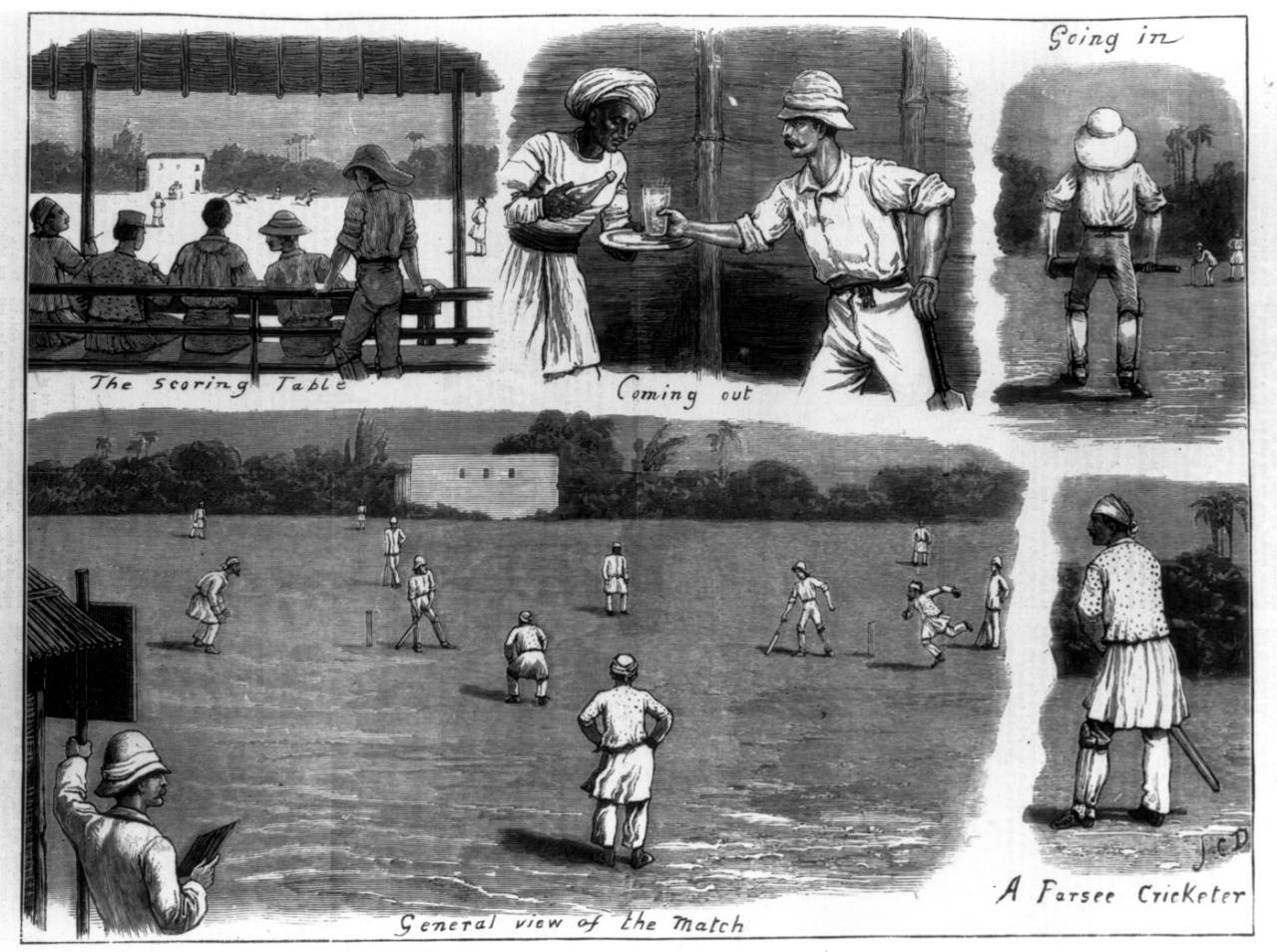

The cornerstone of his wide-ranging work is a study of the game's early development. Taking what he terms cricket's hot spots, Berry analyses why the game evolved, concentrating on England, India, Australia and the West Indies. In England, he presents the Duke of Wellington as a critical supporter of the game at a crucial juncture in its history. In India, it is the relationship between the British and the Parsi community that strengthens the bonds of Empire and ensures that cricket eventually flourishes.

There are some engrossing studies, beginning with the domination of Lascelles Hall in the Yorkshire Pennines - cricket's first hot spot, says Berry - the strongest team in England in the 1860s, all occasioned by the fact that most inhabitants of this unassuming village were hand weavers, and their ground was at the top of a steep hill, so sharpening agility, hand-eye co-ordination and general fitness levels. Berry goes to the ground and bowls an imaginary ball towards the sheep on the moor. Regrettably, he does not test his theory on the present-day locals.

Original thinking has always been one of Berry's most singular qualities. Perhaps only he would discuss whether the Babylonian numeral system would make cricket a lesser game because the nervous nineties would no longer exist

But in Berry's hands, this fulfilling study is much more than a rural idyll. England's historic hot spots are cause, if not quite for savage indictment, certainly for regret. "Very few of the 584 Test cricketers born in England and Wales have reached the top without the help of at least one of these four stepladders," he writes: "1, A fee-paying school; 2, A close relative who has played either Test or first-class cricket, or will do so; 3, Professional football, with the benefits entailed; 4, Being born in Yorkshire or Lancashire where even small communities have a cricket ground. The majority of the male population of England and Wales does not fit into any of these categories. The waste has been enormous."

The social limitations of cricket in England - indeed in many parts of the cricketing world - are scandalous, but Berry does not express the game's shortcomings in such hostile terms. He is no tub-thumper. He is too nuanced for one thing, and in any case this is essentially a book of celebration.

He becomes most assertive when considering how the West Indies were fired to rebel against the "white man's game". The story of

Tommy Burton, one of the first black Barbadian cricketers, is worth repeating. Burton was selected for West Indies' first two tours of England, but he refused to carry the team luggage on the second occasion, in 1906, and was sent home for "attitude problems" and banned from cricket for life in the Caribbean.

His strongest burst of venom is reserved for the match-fixers. "The fixers have lived to fight, and deceive, another day, often in the guise of coach and commentator," he scolds.

At times he seems somewhat conflicted by, on one hand, his desire for cricket to speak to all nations, all social groups, genders and ages, and on the other hand, by his respect for its qualities and its history and the milieu he has so valued. Cricket has given him, like so many, a sense of belonging. He writes revealingly about its comforts in the face of the early loss of his mother (who first took him to watch Yorkshire at Bramall Lane), boarding school life at Ampleforth College, and a traditionally distant academic father.

Original thinking has always been one of Berry's most singular qualities. Perhaps only he would entertain the idea of a chapter on numbers and introduce it with the thought that in the remote highlands of Papua New Guinea the villagers only know to count in terms of "one, two, three, plenty", so any attempt to keep an accurate scorebook is therefore impossible. Or to wonder at length why the hat-trick is celebrated more than four wickets in four balls, or to discuss whether the Babylonian numeral system - which works in 60s and is still used for telling the time - would make cricket a lesser game because the nervous nineties would no longer exist.

He ruminates, too, on the

language of the game, concluding that it has always been tipped in favour of batsmen rather than bowlers, a view predicated on the fact that batting initially was a very hazardous business. "From the beginning, therefore, the language of cricket sympathised with the batsman as the underdog," Berry concludes, Batsmen are given desirable qualities; bowlers can be close to the devil.

It will be a reader with a keen historical bent who shares Berry's detailed interest in the

Kent v England match of 1744, the first game for which a match report survives, and which Berry pores over for a whole chapter. Equal weight is attached to a match between the Parsis and GF Vernon's XI at the Gymkhana Ground in Bombay in 1890. The length of these sections seems at odds with the pace of the book elsewhere.

Bu there is much pleasure to be found here. He concludes: "This game can bring together so many sections of society to play and watch, whether people do so for the camaraderie; or the gratification of physical sensations; or to make a statement about themselves; of their ethnic group, or their country; whether they enjoy the game's language or literature; whether or not they are intrigued by the numbers the game generates; whether they admire the game's ethics, or enjoy its aesthetics; whether or not they are fascinated by the game's psychology; whether they use the game's time frame like a Zimmer frame, as something to cling to in the face of eternity. This sport can support us all. Cricket is the game of life."

There is much to celebrate. On that, many of us will heartily concur.

Cricket: The Game of Life

by Scyld Berry

Hodder & Stoughton

432 pages, £25 (hardback)

David Hopps is a general editor at ESPNcricinfo @davidkhopps