Sixteen years ago - almost exactly - I made my

first-class debut. I was 18, and the memories of that day are so clear that it could be yesterday. I bought a can of Lucozade and a copy of the

Times from the shop across the road in Cambridge, then cycled the mile or so to Fenner's, the famous old ground where the Cambridge University "Blues" play against the inevitably much stronger county teams. I sat in a corner of the dressing room before opening the batting, collecting my thoughts; I walked out to bat to the left-hand side of my opening partner; I didn't take strike, so I was No. 2 on the scorecard; I grounded my bat in the batting crease at the end of every over - even if there had been a boundary.

What I didn't know, on that very first morning of my career, was that my footsteps - so utterly humdrum and banal - would become fixed in stone by my own chronic addiction to superstition. I got a hundred against Glamorgan in that first innings, a blessing in many ways. But I was so superstitious that I couldn't change the routine I had stumbled upon entirely by accident - the Lucozade, the Times, the same corner of the dressing room, the left pad on first, the velcro straps adjusted just the right number of times, the bats lined up on the table, bat-faces staring out into the room.

I try to be a rational person, and I knew, of course, that it was absolutely ridiculous to think there was any correlation between my choice of soft drink and the number of runs I scored. But the rituals became fixed. I was learning the tip of a hard lesson: batting drives everyone a little bit mad, however sane and well-adjusted you start out.

At least I was in good company. Neil McKenzie, the South African batsman, went though a spell of attaching his cricket bats to the ceiling of the dressing room before he went out to bat. Obviously, I can sympathise with the sentiment. But how did he stumble upon the routine in the first place? Was he tinkering around with a bit of interior decorating - would my bat look good dangling here? - immediately before he scored one of his hundreds?

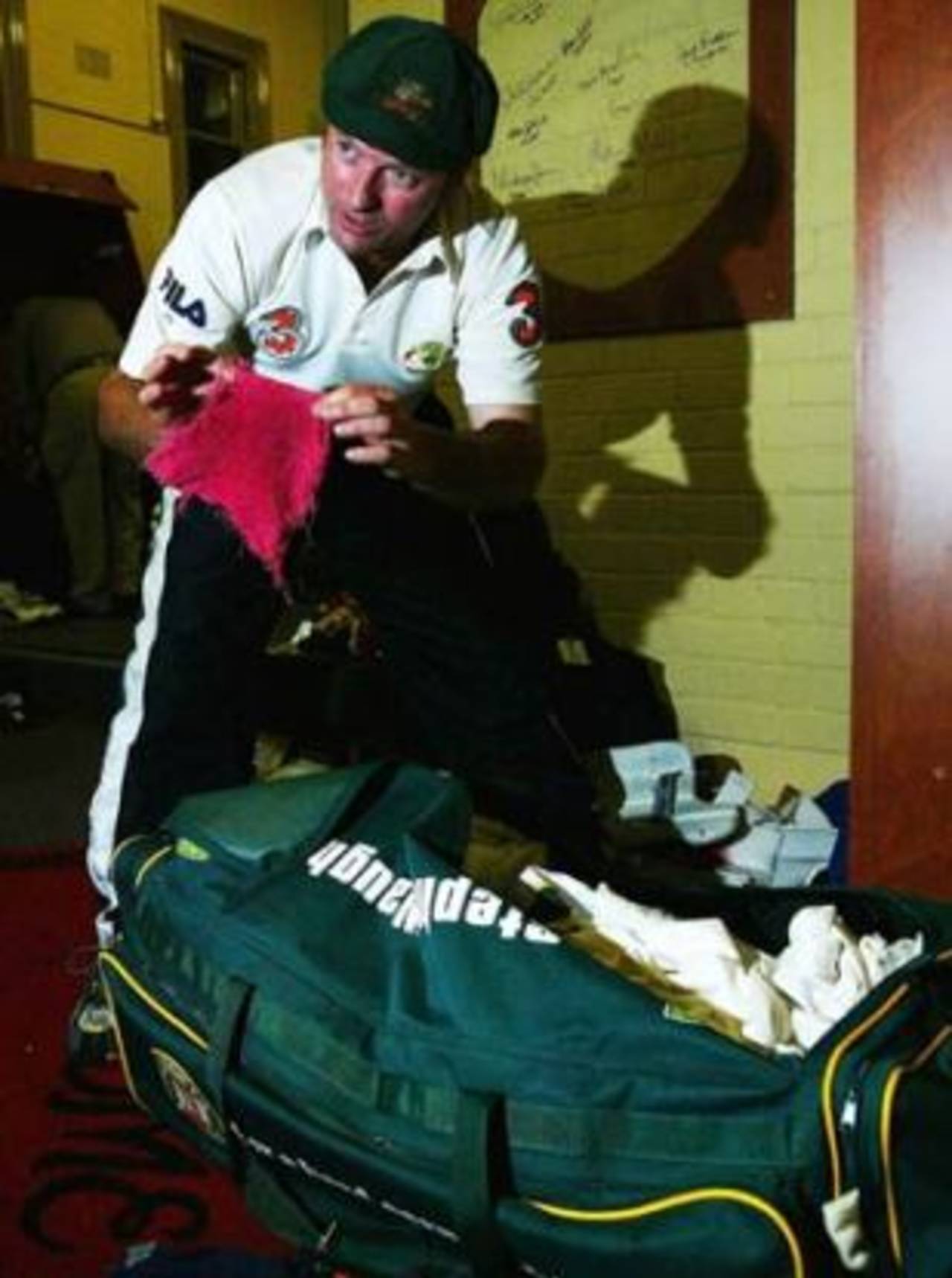

That is how superstitions arise: you have some success and search for explanations in the recent past. Don't be fooled into thinking that superstition only affects the weak-willed. Steve Waugh was the archetypal Aussie battler, but he carried a small red rag in his pocket when he was batting. "It started at the Leeds Test match in 1993, when I was in the 60s," he explained. "I brought it out as a sweat gatherer and I went on to score a hundred." He kept it for the rest of his career.

Superstition doesn't respect rank or stature. Sir Frank Worrell was one of cricket's great statesmen. But when he was out for a first ball duck against Australia in 1951, Worrell changed every stitch of clothing, fitting himself out in a completely new gear. "He walked to the wicket hoping that by discarding his old clothes he would change his luck," we learn from Sir Learie Constantine's obituary of Worrell on ESPNcricinfo. "Not a bit of it! He was out for another first baller!"

Superstition affects great athletes in other sports, of course. You'd expect that most sportsmen would be able to find time to meet the Queen. But the usually unfailingly courteous Rafael Nadal had to skip his royal appointment during Wimbledon because he hadn't met the Queen the day before. He couldn't face interfering with a winning pattern of behaviour. Given the choice between the Queen and his winning routine, routine won in straight sets.

If you really mess up and miss the middle of the bat by a foot, then the ball travels safely through to the wicketkeeper. But if you only mess up by a small amount, and miss the middle of the bat by half the width of the bat face, then the ball catches the edge and you trudge back to the pavilion

But cricket, surely, remains the most superstitious of all sports. Why? Partly because there is more time to observe - well, invent - correlations between patterns of behaviour and runs scored. The Indian psychologist Ashis Nandy has a different theory: superstition is built into the structure of the game because there is such a high degree of luck. Nandy explores the theory in his left-field book The Tao of Cricket: "It is a game of chance and skill which has to be played as if it is wholly a game of skill… Cricket is nearly impossible to predict, control or prognosticate. There are too many variables and many of the relationships among the variables are determined by chance."

It's not all about luck, of course. You need a lot of skill to make a hundred. But you almost certainly need luck as well. After all, how many hundreds are reached without a single play-and-miss? Not many. And yet, as we all know, a play-and-miss is a worse shot than an edge to the slips. Not a worse outcome. But worse in terms of the degree of distance from the batsman's intention (which is hitting the ball with the middle of the bat) and the end result (an air shot). In cricket, if you really mess up and miss the middle of the bat by a foot, then the ball travels safely through to the wicketkeeper. But if you only mess up by a small amount, and miss the middle of the bat by half the width of the bat face, then the ball catches the edge and you trudge back to the pavilion. Go figure.

No wonder cricketers lean on superstition as a crutch. They cannot accept the awful truth - that the game is governed by erratic umpiring decisions, random tosses and unpredictable seam movement - so they invent a coping strategy to persuade themselves they are in control. The umpire won't give me out because I've got my red rag; I'll win the toss because it's my father's lucky coin; I'll make runs today because I've taped my spare bats to the ceiling.

Nandy's thesis goes further. He believes cricket's metaphysics is uniquely well adapted to the superstitious tendencies of the most cricket-mad of all nations: India. As he writes in the famous first line of The Tao of Cricket: "Cricket is an Indian game accidentally discovered by the English."

I'll raise a can of Lucozade to that.

Former England, Kent and Middlesex batsman Ed Smith's new book, Luck - What It Means and Why It Matters, is published in March 2012. His Twitter feed is here